My husband always tells me, “Write about whatever’s on your mind.” Okay, I’ll follow his advice for this week’s post.

My husband always tells me, “Write about whatever’s on your mind.” Okay, I’ll follow his advice for this week’s post.

This short article has stayed on my mind for several days, although not necessarily for a happy reason. The subject is a good one. A study by MIT professor Josh McDermott presented consonant and dissonant intervals to two groups: Westerners and a remote Amazon tribe. It found that the tribe (with no exposure to Western harmonies) had no preference for consonance. But the simplicity of the study’s presentation in the article disconcerted me with its strings of generalizations asserted without support or context. The implied idea that, after centuries of Western civilization, people finally were exploring the topic of consonance and dissonance and its effects, well, that nearly set me off.

In the world of the internet, a study like this gets a lot of cyber spin. The article concludes (here’s where I got disconcerted) that there must not be any inherent qualities to these intervals, in and of themselves, at least not as perceived within the aesthetics of Western music. If their effects are neutral (as they seemed to have been in this study), then doesn’t that call into question the value-based role of the entire major/minor system upon which Western music is based?

No, it doesn’t.

Let’s add some historical context.

First, let’s heartily acknowledge that fascinating music exists everywhere in the world. In any place you travel on the globe, you will find what we used to call native music, folk music, both a vocal tradition and music for instruments honed from natural wood and bone, or strings and membranes made from the skin or gut of some animal.

In fact, in one of the great moments in musicological history, two esteemed researchers, Eric Hornbostel and Curt Sachs, published in 1914 what today would be called a value-neutral system for categorizing the world’s instruments. Published as the Hornbostel-Sachs system, the categories organized all instruments by how the sound was produced: striking a membrane (membranophones), activating strings (cordophones), blowing air through something (aerophones), or hitting a solid substance so as to cause it to sound (idiophones).

Thus the simplest stretched-skin drum in a remote jungle matched up, in a value-neutral sense, with the finest set of concert tympani played by a percussionist in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. And, in terms of construction and concept, acoustics and physics, this comparison works.

But remember, we’ve lived through a cultural revolution of sorts in the 1960s, 70s, and into the new century. Value-based assertions are considered imperial or judgmental or prejudiced or racist or . . . you fill in whatever words you want. It’s far safer to assert that everything is value-neutral and that nothing is particularly better than anything else. Following this logic, a folk-dance pattern in a Slovakian village (complicated, inspiring, and definitely worthy of study) matches in quality and value the rhythmic subtleties carefully crafted by Brahms in his compositions.

Nothing new under the sun.

Beyond that, the author of this article is feeding readers an implication that the effect of intervals on the ear, on the mind and soul, simply hasn’t hitherto been explored or dissected. Today’s gullible and unversed public will likely believe that, thus spreading another misconception like wildfire throughout the cyber-world.

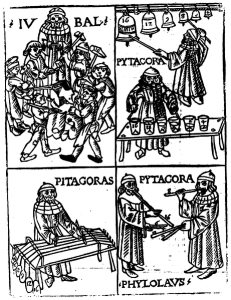

So who first investigated the intervals scientifically and aesthetically? The Greeks, of course (and perhaps others before them, but the Greeks left us the written record). As you might guess, it’s a complex story, and it produced a good deal of the material still taught today in a serious music theory class.

To put this new MIT study into context, one would want to make a better reference to what is already known, beginning with the writings of Pythagoras, for one. The Ancients figured out both the mathematical relationships of the intervals in their rich system of scales and the emotional affect those intervals and scales had on people. The article’s author glosses over these achievements.

There’s a reason why serious study of music begins with a study of the Ancients, particularly regarding what Plato understood about this topic. The potency of his descriptions of the specific effect of different intervals and scales on the human emotions cannot be topped by even the flashiest scientific reports today.

So what am I saying? Musicologists around the globe have long understood that the musical system in Northern India is built on a specific (non-Western) understanding of pitches, rhythms, and acoustical nuances. That music differs, even, from the system developed over the centuries in Southern India. And it certainly differs from the native music in Bali, or the ballads of the Appalachian Mountains. Hornbostel and Sachs helped us see the relative unity of musical instruments around the world, but their understanding and appreciation of those instruments did not transfer into a statement that those musical systems are equal to the musical system that produced the Bach B-Minor Mass. Different, yes. Valuable, yes. Engaging and exciting, yes. But the same in their musical and aesthetic sophistication? No.

As an aside, let me add one of my strongest gripes. It’s so unpopular today, even dangerous, to assert that something is “better” than something else. That’s a principal reason why the core of Western Classical curricula has been tossed from our education systems in most places. It’s also why people heartily praise a completely untutored voice on a popular TV show as “marvelous,” confusing raw talent with hard-earned musical achievement.

Drawing big conclusions on insufficient data.

But I’ll leave that gripe for another day. Back to this MIT study. Let’s expose several more flaws in it, or at least in the conclusions being drawn in this article. First, the study says that the members of the tribe had no difficulty distinguishing consonance from dissonance. This indicates that consonance and dissonance have an objective basis. The listeners merely expressed no preference for consonance. Second, the presentation of isolated intervals should not be confused as the presentation of a musical composition. A juxtaposition of two notes does not equal music any more than two words equals a short story or novel. Music—all music, theirs, ours, everybody’s—exists as a progression of sounds.

Third, Western music cannot be cubby-holed as “consonant.” It thrives on dissonance and the tensions created by the interplay of consonance and dissonance. Perhaps the most dynamic “driver” of musical energy is the establishment of dissonance and the resolution into consonance. This holds true in a Bach fugue, a Scott Joplin rag, or your favorite song from a Broadway musical. The interplay of consonance and dissonance defines Western musical style.

Finally, in the rush to denigrate what they perceive as the cultural myopia of imperial Westerners, the commentators seem to ignore the fact that any remote tribe has its own culture. They are not a blank slate. Yet their aesthetic preferences are assumed to be universal. Did anyone bother to ask: would another remote tribe 50 miles farther up the Amazon River (or similarly remote tribes in Africa or Asia) have the same reaction? The only control group consisted of city-dwelling Bolivians with exposure to Western music. We are left with the implication that one small tribe can speak for all humans who lack exposure to Western tonality.

Western classical music is no longer just Western.

Back to my husband, Hank. He likes to say, quite seriously, that if Western classical music is saved, it will be by the Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and other Far East cultures that have embraced it so enthusiastically. Yes, those non-Western cultures recognize the inherent value in Western music, and their testimony surely outweighs what we can learn from playing a few intervals for a few hours to a small tribe on the Amazon.

You can tell this article disconcerted me, yes? But featuring it this week helps me lead nicely into something I want to share with you in next week’s blog: a musical adventure I learned about from a dynamic young Greek pianist while I was lecturing on a ship in the middle of the Arabian Sea.