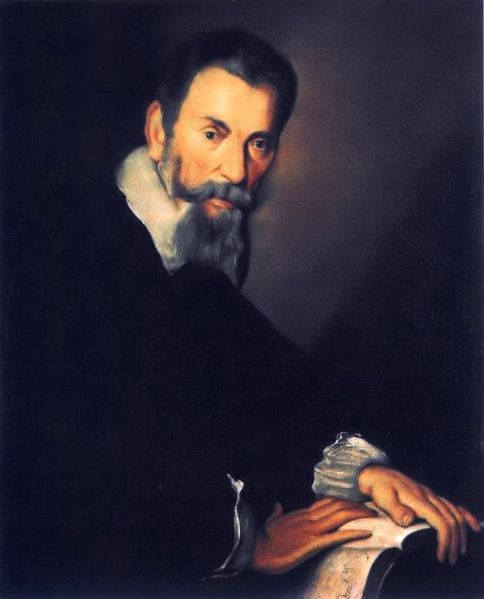

Claudio Monteverdi

Born: 1567 in Cremona

Died: 1643 in Venice

Era: Renaissance/Baroque

Please refer to the Listening Form for further instruction.

Claudio Monteverdi would be astonished to learn that his 1607 experimental opera Orfeo is still performed today. Called a favola in musica (fable in music), his innovative setting of the Orpheus myth contained the seeds of the dawning Baroque style. It foreshadowed ideas that shaped opera for the next 300 years.When Monteverdi turned to writing a new kind of sung drama, he already had experience with theatrical productions, particularly the popular intermedii that featured “pastoral” or idealized country scenes. He was a mature composer, regarded as a master of Renaissance vocal music, especially the madrigal.

Madrigals were popular, complex pieces for singers (without instrumental accompaniment). They were constructed using a set of cleverly intertwined vocal lines in a style we call “polyphony” (literally, many sounds or many voices). In Orfeo, several sections of the story are set in madrigal style, which would have pleased his audiences.

Yet Monteverdi was fascinated by a new style of composing. He became interested in the possibilities of a single-line of vocal melody with simple accompaniment—what is called monody. To us, this might seem ho-hum, but at the time, it was a radical departure from complex polyphonic styles.

There was even a scandal about his writing music in this new style. His own brother had to defend him in the press. Monteverdi stuck with the innovations, though, and wrote several successful dramas before his death in 1643. These works are considered cornerstones of opera history.

Orfeo opens not with an overture such as we would expect today (they hadn’t been invented yet), but with a rousing piece called a toccata. It’s quite simple: a fanfare- passage is sounded and repeated two more times. It’s an attention-getter and definitely announced the beginning of the performance.

A lengthy prologue follows in which an allegorical, or symbolic, character (La Musica) sings about music’s power, using the new sung-speech form of “monody” or, as we call it today, recitative. Audiences judged new works in part by the quality of the words—in this case, the poetry of esteemed poet Alessandro Striggio. Even today, Striggio’s words for Orfeo are highly effective.

Many wonderful scenes will follow, including a pastoral section where characters sing in madrigal style and the villagers dance. But then the news of Erudice’s plight reaches their ears. She has been bitten by a serpent and carried off to Hades (the Afterworld in Classical mythology).

Orpheus cannot accept her loss, and travels to the gates of Hades to find her. He invokes the power of music (in monody) to lull the guard so Orpheus can cross the River Styx. It works, and he retrieves Erudice, but on the condition he does not look back at her while he leads her away.

Of course, he does look, as every character caught in this archetypal dilemma will. He loses her again, and, depending on the ending used in different version of the myth across time, is tormented the rest of his life by his loss or else is transported up to the gods as comfort.

For musicians, the story of Orpheus is significant. It says what modern science increasingly acknowledges about music: namely, that music can reshape our thinking, counter-act violence, and even aid in healing.

While Orfeo may strike today’s listener as “old” in sound, Monteverdi was doing all kinds of innovative things, particularly with his extensive passages of monody. He also designated specific instruments for the various orchestral parts. Accustomed to modern orchestras, we may not perceive his ensemble to be particularly “large,” but it was by the standards of the day.

Returning to the Toccata, the name is derived from the Latin verb toccare which means “to play.” In late Renaissance and Baroque times, toccatas were instrumental pieces that musicians (like keyboard players) used to warm up the fingers and, in the case of lutenists and guitarists, make adjustments in the tuning as they went along. Here, the fanfare-tune is solidly presented and strictly repeated, although with variations in instrumental color each time.

It’s difficult to watch a good performance of Monteverdi’s Orfeo and not be energized. The rhythms of the choral pieces and dance sequences are infectious. They contrast wonderfully with the long stretches of lofty emotions sung in the new recitative style. Monteverdi shows us the world of Classical Antiquity at its best, filtered through the tried and true styles of the Renaissance, and boldly combined with controversial new Baroque techniques.

Listen to the toccata several times. See how long it takes before it has entered your ear. Then, look for other recordings to hear the different ways it is performed. Some ensembles broaden it, to make it more stately. Others give it a jaunty bounce. The use of exact tempo markings (allegro, largo) hadn’t yet come into fashion, so musicians used the nature of the material and their own musical judgment to determine the speeds. Either way, the melody is difficult to forget, once you’ve come to know it.

Focus Works

[catlist name=”focus” numberposts=15]