It’s early in the semester, so few students are thinking about their term papers. But for those of us engaged in work where something written always is due (or overdue), there is no vacation from writing.

Long have I claimed not particularly to enjoy writing. Yet I have spent a good part of my life doing it, in a wide variety of settings and occasionally to my pleasure.

Across time I have learned two things about writing: first, the initial process, for me at least, is messy. Actually, many things I do are messy, and I struggle daily to counter those inclinations. Secondly, the more I like something I’ve written, the more likely it is that it needs to be cut.

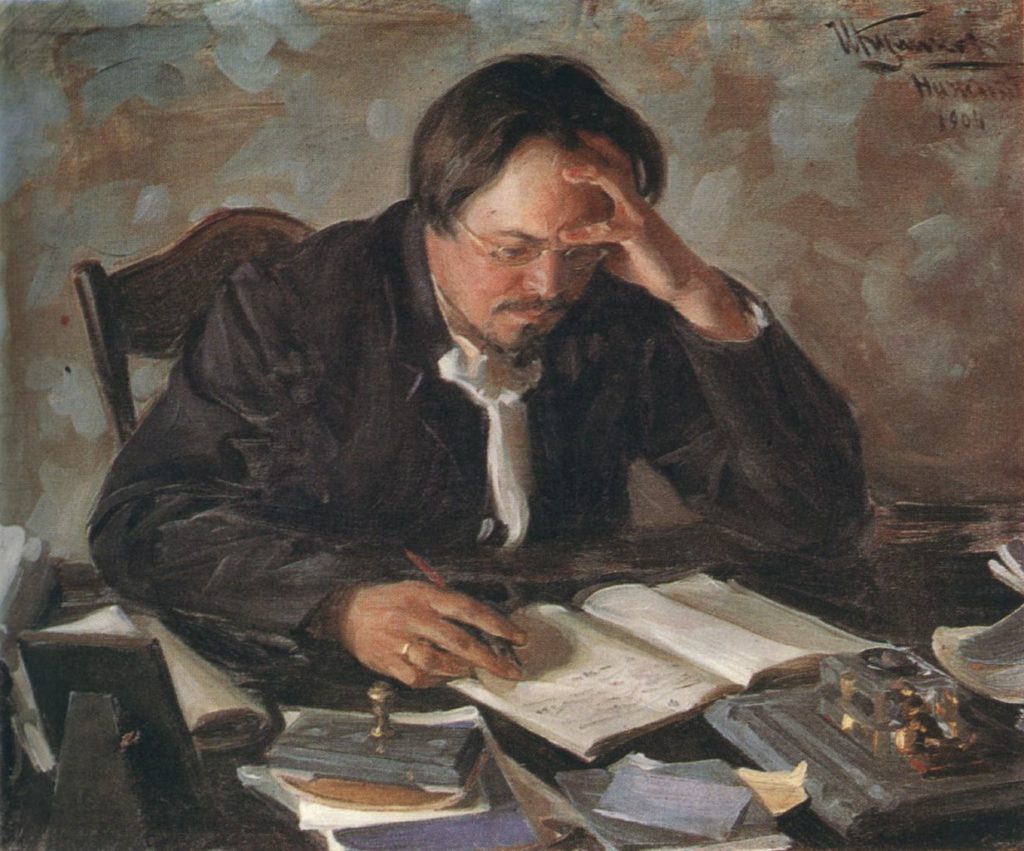

First point first. Whereas some people jot ideas neatly and with ease, or make meticulous outlines that facilitate writing, I approach writing like a person driving an old tractor in high gear, sliding halfway off the seat at the constant bumps in the road. No, that is not a pretty image, nor an admirable approach pedagogically.

Still, once the motor is in gear and I plow jerkily along the pasture, words start to come . . . except they pour forth in mounds, often piling up higher than each spot requires. So, if I were to teach a writing course, I would call it The Art of Cutting. And that brings me to my second point and a story.

Long ago, around 1983, I hosted Dr. Lilian Pruett, the wife of one of my dissertation committee members and herself a celebrated scholar in Renaissance music. I was living in a picturesque apartment in Limburg, Germany, primarily writing my dissertation. She needed to pass a day or two in Germany before traveling for music research to Croatia, then part of Yugoslavia and the land of her birth. Because I did not know her well, and because she was a reserved person (at least in my still-student perception), I was a bit nervous.

As it turned out she was incredibly kind and easy to be with. The afternoon before her day of departure, she volunteered to give a reading to the initial chapters of my dissertation, if I so wished.

I was terrified. I had shown these chapters only to my principal advisor when he was in Cologne for an international musicological congress. The result of that first editorial session still sends chills down my spine and deserves its own post. Suffice it to say, I was void of confidence. Still, the thing needed doing, and there she was: Professor Lilian Pruett, seated in my sun room, smiling and willing to help me with her expertise. How could I say no?

Of the many things I learned about writing that day, one became formative in everything I’ve written since. Commenting about a point spread across two pages, she said that her problem with my flow of words came from this one particular short paragraph in the middle. In her opinion, it needed to be cut.

“Oh dear,” I said in dismay. “Gosh, that’s my favorite part of the whole section. It reads alright, doesn’t it?”

“Yes,” she nodded. But then she asked an odd question. “When did you write it?” Proudly I answered, “Weeks ago. More than a month ago. That was a core part in my first draft of the chapter.”

“I thought so,” she said. “That’s why it needs to go now.”

Rarely have I been as puzzled as I was at that moment. If the sentences were good. and the idea was solid, why cut it? That’s what I wanted to blurt out.

But I did not have to ask. She told me. “It’s old. It’s served its purpose. You’ve written past it now.” I was puzzled still. Written past it? What did that mean?

“The rest of your prose on either side has evolved, but you are clinging to these words because you like them so much. You haven’t allowed them to grow. Initially these words served you; but now, they are in your way.” What a wild notion, I thought.

But it made sense. In my own mind, I could picture some kind of little foot, encased in a tiny, rigid shoe. The rest of the body had grown, but I had not given this foot anywhere to grow by avidly clinging to its good, but no longer useful, wording and content.

So I cut it. The chapter fell in place, and with that cut came more similar cuts throughout the subsequent chapters. The next day, before she left for Croatia, Pruett gave me a maxim that summed up the process: “The more you love it, the more likely it is you need to cut it.”

So, while we teachers set up the grade books and prepare our lectures, it’s not too early to think through our philosophies and techniques for writing. Perhaps this story will resonate with you. At the very least, it is a story I have wanted to tell: a tale of mentoring by an exemplary scholar that has born endless fruit across the decades of my life.

That you shared this with everyone shows what a great artist and teacher you are. Really, it is a brilliant aide for any project- whether it be in writing, painting, music, or research. It’s timeless and universal!

Thank you, Professor Carol. Allow me this opportunity to tell you how wonderful your writing is. As a dear friend of mine would say, “it makes my heart sing!” I am a messy writer, too, and greatly enjoy each meticulously crafted piece from you. The fond memories, the trips to Europe, the rapturous music, the beautiful details… Every experience comes alive and is shared with joy. Looking forward to many more of your musings.

“An old tractor in high gear…” What a perfect image of messy writers. I have always written that way—I just always had a high tolerance for the mess, both on paper during writing AND on the desk. You have to trust that what is truly needed will come to surface from the chaos. However, as a writer I only evolved after years spent working in editorial at a publishing house. Only then did I learn how to really edit and respect that as a very separate process.

Thank you for sharing this. Much of what I say could probably fit in the “cut it” category as well. Message received! Now to apply.