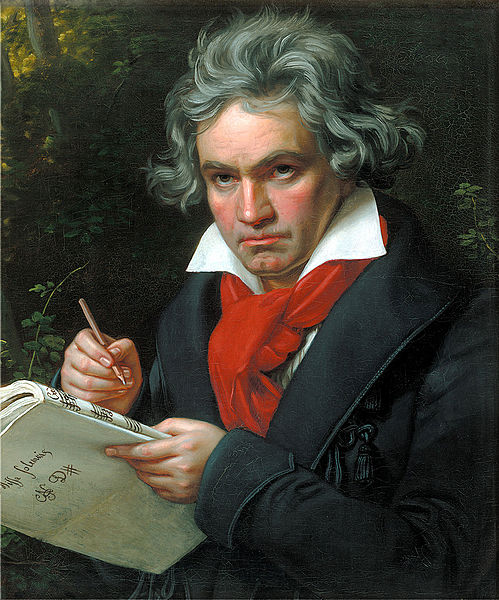

Beethoven, String Quartet Op. 130 (Cavatina)

The late string quartets of Beethoven have a special place in the repertoire. Written in 1825, two years before Beethoven’s death, they are the last major works that he completed.

The late string quartets of Beethoven have a special place in the repertoire. Written in 1825, two years before Beethoven’s death, they are the last major works that he completed.

We tend to divide Beethoven’s works into three periods: early, middle, and late. Early works mostly follow the classical style of Beethoven’s immediate predecessors (and mentors), Mozart and Haydn. In the middle works, Beethoven takes a dramatic turn with innovations that presage the Romantic era. His third symphony, the Eroica (Op. 55) composed in 1804, marks the dividing line. The middle period includes many of the works that are most popular today.

In the late period, Beethoven became more introspective in many ways and more daring in his innovations. He was always more inclined to explore and develop short, punchy melodic statements (think of the 4-note opening of the fifth symphony) than to write flowing melodies, and his late works move further in this direction. The late works can be somewhat challenging for the listener at times. Beethoven blurred the clear lines and symmetries of 18th-century classicism and broke out the standard forms. He increasingly used more contrapuntal textures.

The String Quartet Op. 130 is an excellent example of Beethoven’s late style. Its six movements (not four!) are arranged more like a suite. And the work originally culminated in the Grosse Fuge, a work so challenging that Beethoven’s publisher convinced him to substitute a new, more congenial, finale and publish the Grosse Fuge independently as opus 133. But the elegant and poignant Cavatina (movement 5) will not jar your sensibilities. It is highly lyrical, although it is not a melody you are likely to come away humming. It is intensely introspective. It is asymmetrical and seamless, blurring the lines between phrases. It is unlike anything Mozart or Haydn would have written.

Commentators have found numerous ways to explain the Cavatina. Some focus on the turmoil of Beethoven’s personal life and his relationship with his nephew. Others look to his deafness, and some have even cited it as evidence that the composer had a cardiac arrhythmia. Most seem obliged to quote Beethoven as saying the piece made him weep. I find extra-musical explanations like that only moderately interesting and rarely useful. So, unless you have some particular need to delve into Beethoven’s personal issues, I suggest you just listen and enjoy.