Clementi, Sonata in G minor, Op. 7, No. 3

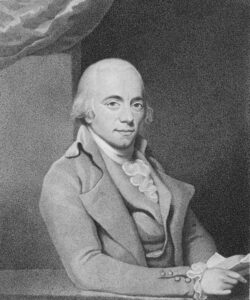

Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) lived 80 years. He was born before Mozart and died after Beethoven. In 1766, he found a patron in Sir Peter Beckford and moved to the Beckford Estate in Dorset where he completed his musical studies. England became Clementi’s adopted home. There he would achieve fame second only to Haydn.

I was doing some research that led me to Clementi and decided that it was time to include him in this series. If you know something by Clementi, it’s probably one of his sonatinas that you have learned early in your piano studies. I confess that the sonatinas did not inspire me to dig much deeper into his works.

A sonatina is simply a short, easy, or light sonata. A sonata is generally a multi-movement instrumental work, usually for solo piano or another solo instrument with piano accompaniment. Compositions entitled “sonata” were written in the Baroque period, but the form we know today is strongly associated with the Classical era—beginning with Scarlatti and C.P.E. Bach and becoming highly developed by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Clementi. Sonatas written by the latter two spill over into 19th-century Romanticism.

Clementi’s reputation was strong during his life, but his fame in posterity was affected by an event that happened in Vienna on Christmas Eve 1781. Emperor Joseph II arranged a piano competition between Clementi and Mozart, both of whom were in their late 20s at the time. Both had strong reputations as virtuoso players. From later writings, we learn their thoughts on that evening’s competition. Clementi was impressed by Mozart, reportedly saying, “Until then I had never heard anyone play with such spirit and grace.” Mozart, on the other hand, gave faint praise to Clementi and dubbed him “a charlatan, like all Italians.” Mozart, I should add, was judged the winner of the competition.

Clementi composed the opus 7 sonata featured here in 1782 while still on his extended visit in Vienna. It is short and compact, but with much more to offer than his sonatinas. Although this sonata stays within the bounds of the Classical form and harmonic vocabulary, we hear many things in it that presage Beethoven’s innovations, who then was only an 11-year-old boy. Beethoven’s sonatas would later break free of Classical constraints and expand the sonata significantly in length and complexity. Clementi’s endings to his sonatas, somewhat abrupt and anti-climactic, were nothing like Beethoven’s elaborate final sections (codas). But Clementi deserves, and should be accorded, credit for having a strong influence on the early keyboard works of Beethoven and over piano composers in general well into the 19th century.