Debussy, La mer

The sea is beckoning, and I’m going to finish out this pre-Lenten season with more maritime music. Impressionism lent itself well to depicting various aspects of nature, perhaps none better than the sea. And the prime representative of Impressionism in music is Claude Debussy (1862-1918). (Debussy rejected the impressionist label, but it’s really not up to him to decide.)

La mer was written in 1903-1905 and revised in 1909. This is the revised version. It consists of three movements with descriptive titles:

- From Dawn to Noon on the Sea

- Play of the Waves

- Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea

Debussy styled it as “symphonic sketches,” wanting to avoid the terms “symphony” (which it clearly is not) and “symphonic poem” (which it mostly is). But “symphonic poem” conjures up the works of Liszt and Strauss and the then-dominant German style of Wagner, and Debussy, along with other impressionists, were trying to break free of Wagnerism.

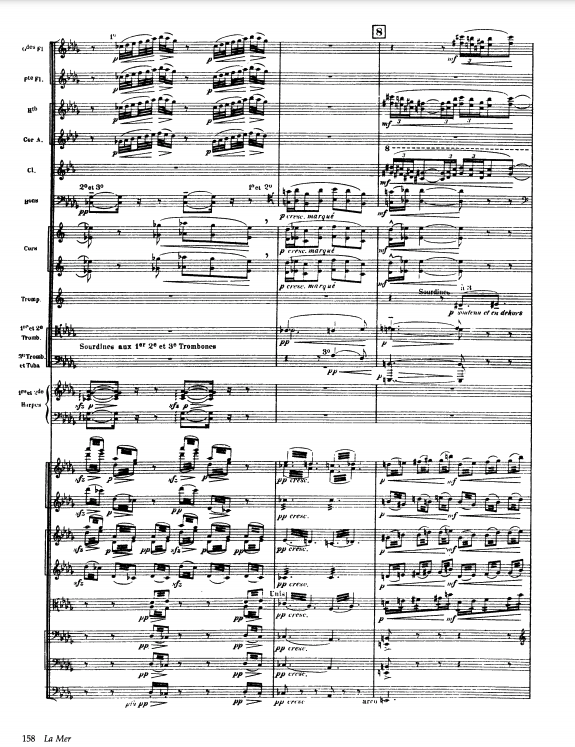

So how does one depict the sea in music? In case this is on your to-do list, you can learn something from Debussy. As a foundation, you will want lots of swells–crescendos and decrescendos–to convey the waves. Melodic figurations should constantly move up and down in contrary patterns and cross currents. (Sea waves don’t all move in the same direction or at the same speed.) Tremolos can represents the unsettled surface and foam. Add in an occasional gong or cymbal for splashes. And, especially if you’re an impressionist, use whole-tone melodies to keep them from ever coming to rest.

Even if you don’t read orchestral scores, a quick glance at a typical page of La mer will reveal a picture of the sea.

Even if you don’t read orchestral scores, a quick glance at a typical page of La mer will reveal a picture of the sea.

La mer always calls to mind my professor of conducting and score-reading, George Lawner, who was of course Austrian and knew virtually everything having to do with music. Graduate conducting class had only two or three students, and we took turns conducting and playing the score on his two pianos. Score-reading is not so much about piano technique as it is in quickly distilling what you see to its essence–easier to do with Haydn than with Debussy (or Strauss or Stravinsky). Lawner demonstrated what he expected one day with La mer. As he convincingly played it on the piano, he showed us how we must turn our own pages with one hand, perhaps with time to take a sip of coffee, while continuing to play seamlessly with the other. We managed to approximate some of that, but without any of the calm confidence.