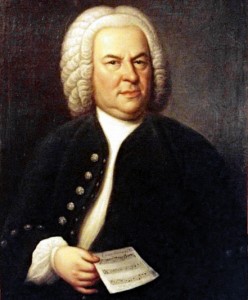

Johann Sebastian Bach

Born: 1685 in Eisenach

Died: 1750 in Leipzig

Era: Baroque

What is a Toccata and Fugue?

The word “toccata” comes from the Italian toccare (to touch). This type of instrumental piece was designed to highlight the performer’s technical ability—literally, how well the player could “touch” the instrument. The toccata usually has a free form that sounds improvisational. The toccata is discussed in Unit 5.

The term “fugue” is derived from the Latin fugere (to flee) or fugare (to chase), and “chase” is a good visual image for what happens in a fugue. A fugue is somewhat like a round, such as “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” where each voice enters at a different time but sings the same thing – only a fugue follows much more complicated rules.

Taken together, the free style of the toccata is coupled with the rule-bound style of the fugue, making an interesting contrast. Ecstatic vs. Didactic.

Counterpoint

Counterpoint literally means note against note. In counterpoint, individual melodic lines are pitted against each other. For a simpler demonstration of counterpoint, listen to one of Bach’s two-part inventions and notice how the “left hand” imitates the “right hand.”

Instead of a single melody with supporting accompaniment (homophonic music), the voices in a contrapuntal work are essentially equal and independent. Making the voices fit together requires great skill.

Now, back to the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. Watch this animated video:

The toccata ends and fugue begins at 2:50.

Understanding the Toccata

You may recognize the opening motive of the toccata. It is perhaps the most famous theme for the pipe organ and become something of a cliché in film.

Notice the various types of imitation and contrast. The opening motive is stated three times at successively lower pitches (with a slight variation). You will frequently hear short melodic figures stated twice with the second statement changed in some way. Listen, for example, to the statement at 0:45 on the video below repeated at 0:53. Notice also the contrast between running melodies and block chords (e.g. 1:00 and 1:08).

Understanding the Fugue

This fugue has four distinct voices or parts. Some fugues have three voices and some more than four, but each voice is equal in importance and follows the same rules. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish the individual voices on a keyboard instrument, but the animation in the video assigns each voice its own color.

The fugue begins with a single voice stating the “subject” (2:50). The second voice enters at 2:56 with the “answer.” The answer is (in this case) an exact duplication of the subject, but at a different pitch. The third voice enters later at 3:13 with a restatement of the subject, and the fourth voice enters with a restatement of the answer at 3:46. This sequential entry of voices is called the fugue’s “exposition.”

After the exposition, a fugue will typically develop the themes in a variety of ways. You will hear the subject and answer coming back in different keys. Notice also how the subject is sometimes transformed: chopped into smaller pieces or turned upside down. In between the statements of the fugue subject that follow you may find passages of seemingly unrelated music called “episodes” (e.g. 4:06-4:32 and 4:41-5:14).

Near the end of a fugue, you are likely to hear the subject and answer coming back frequently, the statements closer together, perhaps abbreviated, and sometimes overlapping. See how many entries of the subject you can find from about 5:14 through 7:12.

After 7:12, Bach brings back the toccata form as a “coda” to end the piece.

Now watch the toccata and fugue performed on the organ.

Focus Works

[catlist name=”focus”]