Recent conversations with a close friend have set my thoughts directly on this question: what obstacles keep people from appreciating the arts?

The first bugaboo, of course, is the verb appreciate. To me, it’s an obstacle in and of itself. When combined with words like music and art, appreciate seems to transform something joyous and natural into an artificial structure capable of torture.

The first bugaboo, of course, is the verb appreciate. To me, it’s an obstacle in and of itself. When combined with words like music and art, appreciate seems to transform something joyous and natural into an artificial structure capable of torture.

Torture? Well, ask anyone who recalls a poorly taught high-school or college class in music, art, theater, or dance appreciation. They likely finished their final exam hoping to avoid these arts forever. Of course, others recall glorious experiences where they had their eyes, ears, and minds opened by skillful and passionate teachers. A life-long love of the arts is set in motion by such teachers.

At the root of appreciate is the Latin noun pretium, or “price.” So, one technical way to define appreciate is “to determine or set a proper value to something.” We see how this translates into determining the monetary value of a sculpture, for instance. But what about a lullaby? A folk dance? A children’s puppet show?

A more useful definition would be the idea of assigning to the art work a proper aesthetic or cultural identity, i.e. setting it high (or low) on a particular scale of values. And, yes, despite what modern critics preach, there are scales of values established for art over time. The standards of “good” or “significant” are not arbitrary, emotional, or solely individual (sorry).

Still, the value of appreciation most teachers seek to inspire is love—love of the arts. Excitement about the discoveries to be made there. Wouldn’t it be fun to attend classes sporting titles like “Falling in Love with 19th-Century Paintings” or “Losing Your Heart to Russian Ballet”? Or even “Discovering Why You Like the Sound of Trumpets better than Violins.” These are more apt goals, to me, than appreciating.

History is my term of choice: music history, dance and theater history, art history. Yet, “history” strikes young people as referring only to experiences from the past that are no longer relevant. Tell that to college horn players who have just performed Mahler’s Fourth Symphony . . . once they’ve recovered enough from the emotional drain to be able to speak coherently.

Here’s the thing. In learning to “appreciate” art, we have to close gaps for most people. The causes of the gaps are easy to identify. Today’s “every man” does not grow up around theaters, museums, concerts, and dance studios. The popular culture explodes with things ugly and demeaning, not beautiful and inspiring. Crass, violent, and rude are enshrined in the images that inundate us today.

Plus, people have become fully alienated by the nonsense promulgated by the elitists. Critics respond more to vagaries of the Academy than to the response of the viewer’s heart. Yes, it’s sometimes useful to read “educated” responses—reviews, scholarly assessments. It can be interesting. It can even be comedic. (Did this critic and I attend the same performance? Or view the same painting?) But critics rarely draw people who are inexperienced or skeptical into a love for an art form.

The educated class has always influenced the standards of visual and performing art. But the beauty of the art still naturally communicated itself to most people. Artists want to reach a general audience. They have to respond to the desires of patrons, but they want, and need, to connect with the people viewing and experiencing their arts.

This natural pattern experienced tremendous disruptions beginning in the early twentieth century (particularly after the First World War). At that point, massive movements in abstract art, atonal music, and theater of the absurd ran the general audience out the door. The art screamed: “You don’t like this because you are too stupid to understand what it means!” And the general public yelled back. “Fine, I prefer this kind of ‘stupid’ to what you’re trying to pass off as art!”

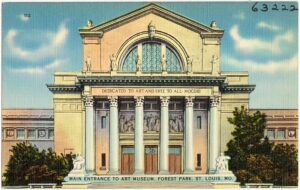

Over the next weeks I will be writing more about visual art. I’ll share some of the adventures in my journey to “appreciating” painting and sculpture. Growing up without any background in the visual arts, I was lost at sea when it came to the subject. I even lacked the basic terminology that you’d expect a high-school graduate to have back in the 1960s (when high-school education was routinely rather good).

Dodging and fakery helped me cover up my ignorance . . . until it didn’t! But that’s a story for a different time. What matters to me most, now, is helping others set aside the things that distance them from the arts. I want to help people plow through the obstacles that keep them from forming a relationship with art, whether a positive or negative relationship. (Negative reactions to an art form can also be valuable!)

I hope you’ll enjoy where these threads go.