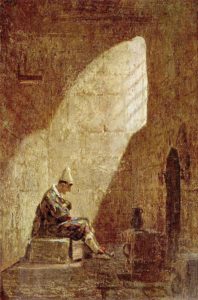

Using a lone figure illuminated by dusty rays of light, the painter Karl Spitzweg juxtaposes the tumult of human consequences against Mercy’s irrevocable dawn.

Using a lone figure illuminated by dusty rays of light, the painter Karl Spitzweg juxtaposes the tumult of human consequences against Mercy’s irrevocable dawn.

Here we see a man who, only hours before, was cavorting in full-blown pleasure as Carnaval’s excesses wound to a roaring end. He may have been a costumed reveler, swirling with friends amidst a cascade of Bratwurst, schnapps, and ancient rowdy tunes. Or he may have been a hired performer, a jester exhausted from working the long days of celebration, who somehow got on the wrong side of things.

Now, though, he sits in a dungeon (Kerker), according to the official interpretations of this painting. The light that streams onto him expresses the harsh reality of morning or, as a popular Carnaval song states, “Alles ist vorbei” (“the unrestrained festivity is over”). His hope now lies in the faint light that proclaims the morning known as Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent.

Lent is the longest liturgical season, a 40-day period characterized by prayer, fasting, and penance in preparation of Easter’s miracle. And while Spitzweg’s painting may well be set in a dungeon, I saw it differently upon first glance.

The figure, to me, was seated not in dungeon, but in a reclusive spot along a city wall, or in a courtyard, perhaps near a cathedral wall. Imprisoned he might well be, but imprisoned by his failings, his sin, rather than by stone cold walls. And while we don’t know how this story will end for our fellow, we each know the feelings he expresses: a rueful recognition of having crossed from what the German’s call Narrfreiheit (Fool’s Freedom) to a point where penance is one’s only hope of rescue.

People often encounter Spitzweg through his tender iconic masterwork The Poor Poet (1839). I certainly did, and initially viewed his artistry solely as an expression of the graceful, intimate style of the Biedermeier Era in early 19th-century Europe.

But later I came to see his depictions of social and individual predicaments as more realistic and psychologically nuanced. Insofar as this painting, Spitzweg invites us to enter and sit quietly on an adjacent ledge. We might be tempted to ask this sad fellow “What happened?” But more likely we would be lost in our own thoughts, bringing our own spiritual weariness and human errors into the same light that illuminates his contemplation.

Art conveys what words cannot. And when we view paintings like Aschermittwoch, we easily can imagine ourselves sharing the canvas with the figures painted within.

May Spitzweg’s depiction of Ash Wednesday speak its own strong message to you during this Lenten season.